Masterclass: Artistic Programming for Subscription Concerts

Creating balanced artistic programming that fits the orchestra, community, and vision of the organization is an art unto itself. Young conductors, as well as seasoned professionals, can struggle with creating compelling programs that build the artistic achievement of the ensemble that leads to an increase in ticket sales and artistic vitality for the organization.

Programming Philosophy — Two Analogies

The first step in creating satisfying programming is to develop a philosophy. Musical works are not just a particular duration of time but have weight, texture, flavor, and color. I think about creating a satisfying artistic program in the same way that I think about creating a satisfying meal; The trick is to pair foods (musical works) that complement each other, are balanced, and are digestible in one evening. The main thing to avoid is having too many main courses in one evening (i.e., a Mahler symphony followed by a Bruckner symphony just isn't digestible by anyone!).

I recently heard a different take on a programming philosophy that I liked: Imagine that the various works that you are considering paring on a program slide up next to one another at a bar. What would these works have to say to one another? Are they so different that they cannot carry on a conversation, or are they so similar that the conversation is boring? Or is there some kind of thread that connects them such that their discussion is engaging?

Both of these programming philosophies are helpful to consider when putting together programs. Furthermore, audiences love to learn how the given works on a program complement each other — it provides listeners context and a point of departure that dramatically enhances their concert experience.

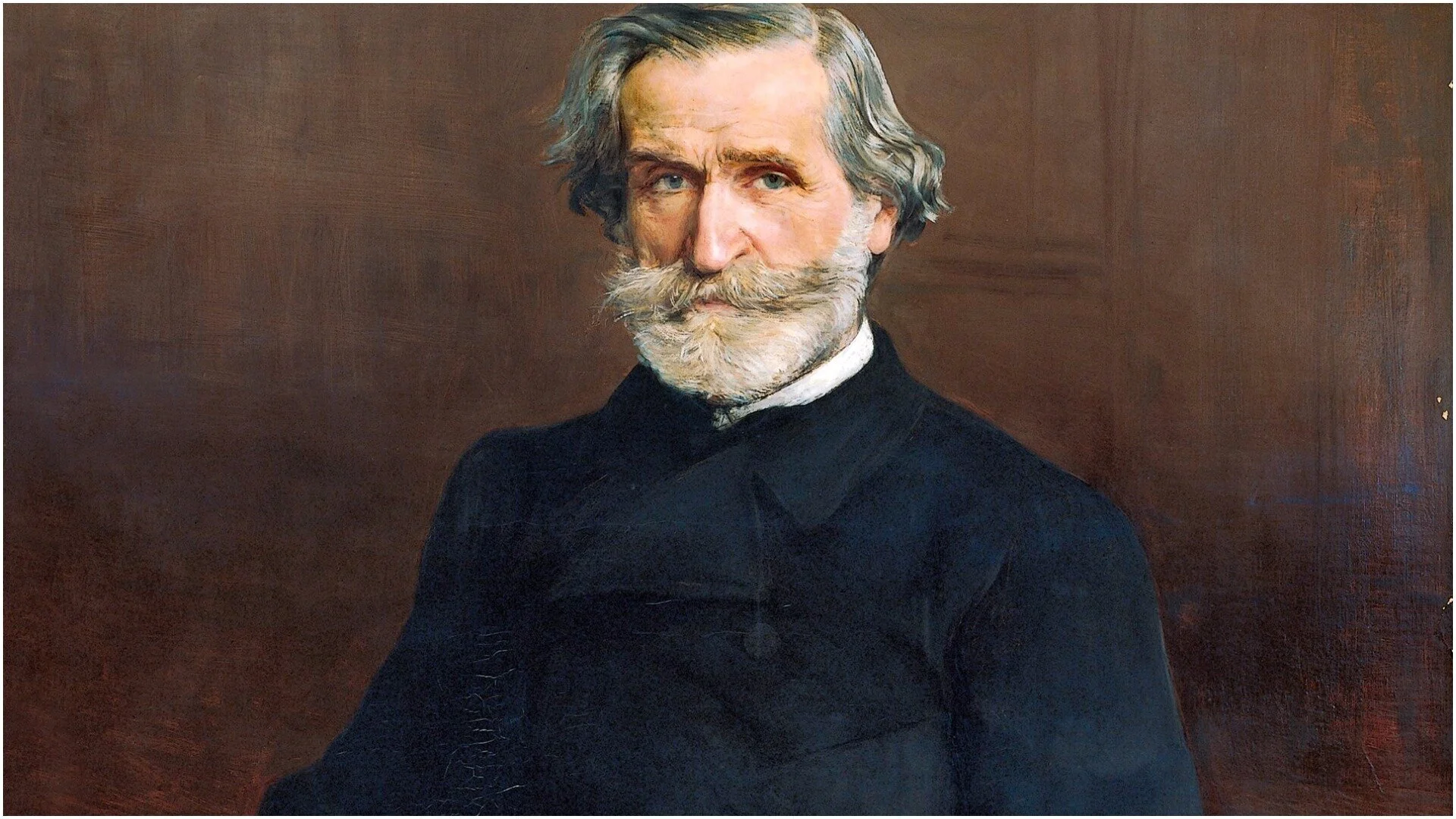

Giuseppe Verdi

Start with Music that Resonates with You

The pieces that you program will reflect who you are as an artist. Therefore, begin your programming with the music that resonates with you artistically.

Recently, I revisited a piece by one of my favorite American composers, John Corigliano's The Red Violin Chaconne. I wrote the work down on a document that I keep in a folder on my computer called "programming." When considering which works to pair with Corigliano's work, I considered many different questions: Where does it belong in the program — before or after intermission? Can it finish one of the halves? What overture should come before it? What is the thread that takes us through the performance? What other works have that kind of cinematic drama? What other composers may complement the given composer that I am programming? I wrote several different drafts of programs that could include the work. Once I was satisfied with the weight, duration, scope, and artistic thread of the program, I knew that I had a winning plan. What I eventually arrived at was:

VERDI La forza del destino

CORIGLIANO The Red Violin Chaconne

PAGANINI "La Campanella" from Violin Concerto No. 2

RESPIGHI Pines of Rome

If these pieces slid up next to one another at a bar, they could talk about Italy, fate, and destiny — and there were so many different weights, colors, and textures that made this a very satisfying program for our audience. Additionally, I was able to "check off another box." By including a work by a living American composer that had aleatoric features, I was able to further the artistic achievement of our musicians and widen the musical palette of our audiences. By carefully curating that experience, I am convinced that a brighter future for live symphonic music was achieved.

Programming with your Musicians in Mind

When you have a large orchestra at your disposal, and musicians who desire to play, you must consider the music on the program from their perspective. How much or how little do they play? How physically taxing are their parts?

Consider the endurance challenges that a given program places on individual players: Beethoven's 7th Symphony is particularly challenging for the horns. Programming a work on the first half that allows them to keep the necessary reserves for the Beethoven is essential. If I programmed Dvorak's 9th Symphony, I would consider the entire program from the vantage point of our tubist, who only plays a few notes throughout Dvorak’s work. What other repertoire could I pair with the Dvorak to engage that player more?

Working within Constraints

Often, we have to work within constraints — rental music budget, the abilities of given players within the ensemble, size of the ensemble, budget for import/substitute musicians, number of rehearsals, etc. are all limiting factors. I always like to keep in mind that the great master, J.S. Bach, created some of the greatest music within some of the most rigorous constraints. I would encourage all conductors to embrace, rather than bemoan, the constraints that are put upon us. I have found that the limitations that I program within are a helpful tool that stimulates my creativity.

Other Important Considerations

There are various aspects to consider — guest artists, regional/national holidays, new music, and what repertoire the orchestra needs to further their artistic excellence are all important to consider as part of a well balanced season.

Guest Artists: piano, violin, voice, and cello are the solo instruments that consistently sell the most numbers of tickets. Also, the organization will often see a spike in attendance when collaborating with choirs. While programming works for these guest artists/organizations can help sell tickets, there is something to be said for featuring other solo instruments that are a bit more off the beaten path. Percussion concertos, wind soloists, or concerti composed by living composers for some of these instruments offer a variety that is critical for staying fresh during a season.

Conclusion

No one concert should attempt to have "everything for everyone." That said, it is important that throughout the course of the season, there is something for everyone. Some audience members only want a steady dose of Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms, others crave new music, others feel — rightly so — that orchestras have a responsibility to present music by minority composers. I often ask myself: If we don't offer new music that furthers our art form, who will?

Whether programming new music or the warhorses of the symphonic repertoire, it is critical that you begin by meeting your audience where they are. Once trust is built, you will be able to use programming to keep your organization on the cutting edge in the field, in the spotlight of your community, all while creating buzz and building audiences.